An introduction to independent prescribing

Independent prescribing is prescribing by an appropriately qualified practitioner responsible for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions, and for decisions about the clinical management. Independent prescribers can prescribe any medicine for any medical condition within their competence.

In 2009, the Department of Health (DH) published a report looking at the use of medicines by the allied health professions (AHPs). The report looked at whether prescribing and medicine supply mechanisms for AHPs should change to address patient and service needs. It found a strong case for extending independent prescribing to chiropodists/podiatrists and physiotherapists. In July 2012, the DH announced that legislation would be passed to allow appropriately trained chiropodists/podiatrists and physiotherapists to act, and be annotated on our Register, as independent prescribers.

As a result of this new legislation, the HCPC developed and published standalone standards for prescribing. We also amended the approval process for supplementary and independent prescribing (SPIP) post-registration programmes, which was reviewed in the 2013-14 academic year.

Here, we summarise the review and its key findings. The full report is available to download here.

WHEN…

When did the HCPC’s standards for prescribing come into effect following the revised legislation?

As part of the legislative change, we produced standards for prescribing. These came into effect from August 2013, following the legislation passing.

To develop these standards, we engaged with stakeholders and undertook a public consultation. The standards cover two areas: standards for education providers and standards of SPIP prescribers. The standards for education providers are based on our standards of education and training, whilst those for all prescribers are proficiency based, and expand upon the standards of proficiency required of chiropodists/podiatrists, physiotherapists and radiographers who undertake supplementary prescribing.

WHY...

Why does the HCPC have an amended approval process for SPIP post-registration education and training programmes?

The development of this amended approval process was a direct response to the DH changes to prescribing legislation in 2012.

It was already commonplace for education providers to deliver independent prescribing (IP) programmes for professions that we don’t regulate (pharmacists and nurses) and supplementary prescribing (SP) for ones that we do (physiotherapists, radiographers and chiropodists/podiatrists).

However, we needed to be sure that independent prescribing could be supported for our professions and in relation to our prescribing standards. As we already approve SP programmes, we were satisfied that new independent prescribing programmes would already meet some of the standards for prescribing. We were also satisfied we didn’t need to conduct a full approval visit to assess them - hence the need for an amended approval process.

This gave eligible education providers the opportunity to gain approval for prescribing programmes in a significantly shorter timeframe than our standard approval process. In fact on average, programmes were approved ten weeks after their documentary submission – less than half the average time taken for programmes via the full process (22 weeks).

This really demonstrates how we’re able to amend our processes to support the work and initiatives of health and care providers.

WHO…

Who did the legislative changes affect and how did this impact education providers?

The changes to prescribing legislation meant that our chiropodist/podiatrist and physiotherapist registrants could act as independent prescribers once appropriately trained and annotated on our Register.

Prior to, and soon after, the legislation being passed, we wrote to education providers which delivered approved supplementary prescribing (SP) programmes to let them know how the amended approval process would work. We also advised them we would assess their programmes against the newly published standards for prescribing.

Our process reduced the burden of work required for education providers to evidence how they met the required standards when compared to the full approval process. This was because they were only required to focus on the standards which were directly impacted by the introduction of independent prescribing.

WHERE…

Where did the HCPC find its visitors for the approvals and monitoring work?

We work with visitors who make the assessments of programmes to ensure they meet our standards. For prescribing, we set rules about selecting visitors for this specific area of approvals and monitoring work.

Our visitors work together in pairs to make an assessment. At least one of the visitors had to be from a non-medical prescribing profession which was entitled to undertake independent prescribing training (a nurse or pharmacist). This visitor was required to be registered, with the entitlement recorded on their respective register.

We also recruited independent prescribing visitors to competencies that were based on the competencies for the visitors of our 16 professions.

WHAT…

What were the key outcomes of the amended approval process?

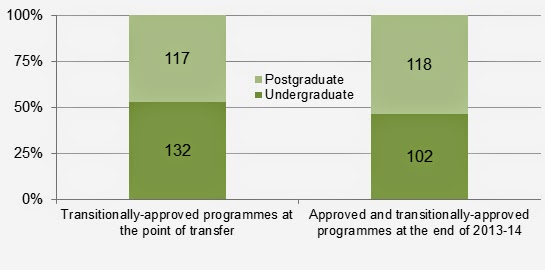

We reviewed 100 prescribing programmes at the assessment days in November 2013.

Visitors were able to request further documentation if they were not satisfied that a standard was met following their review of the documentation. Visitors could also recommend a full approval visit if there were issues remaining following their assessment of a programme. 62 per cent of the programmes assessed met the standards for education providers without the need for additional documentation, as demonstrated in the graph below. This outcome contrasts with the full approval process, where only three per cent of programmes visited in 2012/13 were approved following our first assessment.

So why was this?

There are a number of reasons:

- Education providers were not fundamentally altering their existing prescribing provision to incorporate independent prescribing.

- All of the education providers that engaged with this process ran existing HCPC approved SP programmes, and many ran IP programmes for nurses and pharmacists.

- The education providers were already familiar with our standards and processes.

The outcome of approving these programmes is that individuals from the relevant professions can have their registration record annotated as an independent prescriber, once they complete the relevant training. To date, we have updated the records of 150 registrants with the independent prescribing annotation.